HIV meds are technically still available, says a South African services provider living with HIV, but she adds that the countless workers who helped deliver them are now jobless

In the wake of the Trump administration’s widespread cuts and limitations on PEPFAR, the U.S. global AIDS relief program that has saved millions of lives and prevented countless new HIV acquisitions since President George W. Bush started it in 2003, some countries are being hit harder than others. For example, Nigeria and Kenya are among nations running out of actual HIV meds, the BBC reports.

Meanwhile, unlike in many of the poorer countries in Africa, where PEPFAR provides HIV drugs, the government of South Africa—the richest country on the continent where about 5.6 million people are on HIV treatment—pays for about 80 percent of HIV meds and other services itself. But the country still relied on PEPFAR to fund a variety of prevention tools, including the prevention pill regimen PrEP, and paid thousands of linkage-to-care workers who staffed HIV clinics in the country’s hardest-hit areas.

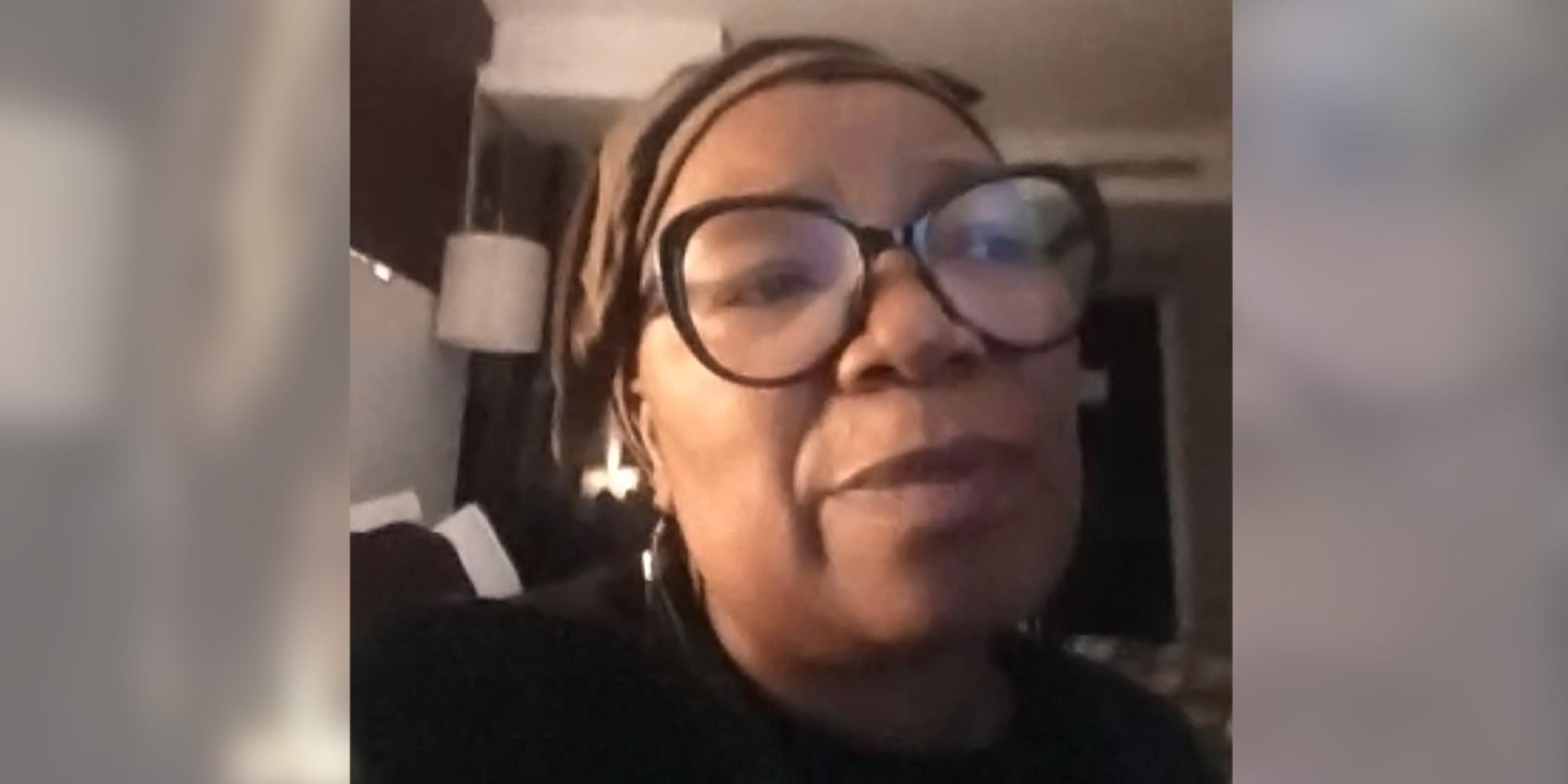

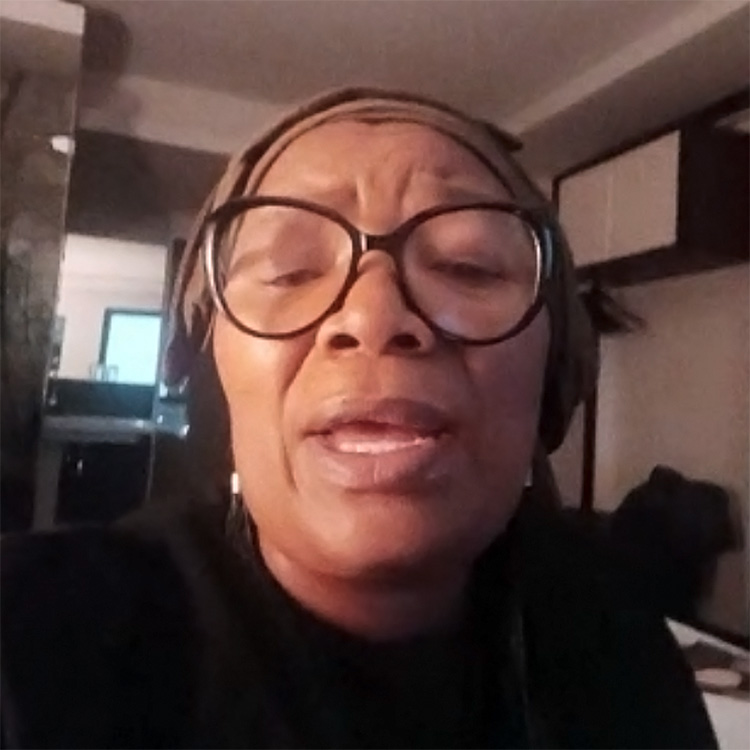

Now that help is gone, which has shuttered clinics throughout the country and led to a drop in HIV testing, care and treatment, as well as a disruption to mobile clinics and drop-in centers. On Tuesday, March 18, POSITIVELY AWAREe spoke via Google Meet with Nombeko Mpongo, a community liaison administrator, herself living with HIV for 28 years, for Cape Town’s Desmond Tutu Health Foundation, which conducts HIV research and services and is a kind of hub for HIV clinics in and around Cape Town. She described a system that, while still able to technically get people with HIV their meds, has been handicapped and thrown into chaos by the abrupt PEPFAR cuts, leaving many of her colleagues in the field—many of them also living with HIV—without jobs. Toward the end of the interview, she broke into tears.

Ms. Mpongo, thank you for taking time to talk today in a stressful time. Technically, South Africans living with HIV still have access to HIV care and, to some extent, even PrEP, yes?

Correct. What’s changed is how treatment is now dispensed. People from the LGBTQ sector, mostly gay men, and also sex workers, were getting their meds at two LGBTQ-specializing clinics, the Ivan Toms Men’s Health Clinic and Wits RHI, which were both funded by PEPFAR. But after the Trump PEPFAR freeze, they were told not to come into the clinics. And the staff were instructed to stay away because there was no more work for them. Those who showed up for appointments found a clinic closed just out of the blue. Now the government is under pressure to employ those people.

Does this just apply to gay men with HIV, or everyone?

Those two clinics that completely closed served mostly gay men. But all 11 clinics that I work with have been affected by the shortage of staff. Because most staff members were coming from a particular NGO [non-governmental organization, or a nonprofit/community-based group] called Anova.

But the people who went to the two gay-serving clinics are still getting their HIV meds?

Technically, yes, because they’re allowed to go to other clinics. But those are the clinics they initially ran away from because of how service was delivered there [meaning, not LGBTQ-sensitive]. And that is going to lead to poor adherence, because they won’t go there.

Were the two LGBTQ-serving clinics closed completely because of the U.S. order to PEPFAR recipients to not serve key populations like men who have sex with men and other LGBTQ people, and sex workers?

Yes.

Were men who have sex with men also getting their PrEP at those two clinics?

Yes.

Are they still able to get their PrEP?

It’s going to be difficult. We don’t know if they’ll go to the other clinics where they’re supposed to go now. But we know there’s going to be hesitancy. So we are there to really make sure that the public health department staff are sensitized [to LGBTQ people]. People are going to die. The people who went to Ivan Toms and Wit RHI are not going to find it easy to go to a normal clinic.

You said that you and other people are trying to make the clinics more sensitive toward LGBTQ people so they’ll actually go there?

We are trying our best to familiarize them with the situation. But starting to work with them is frustrating for me. I went to one of them because I needed one of our participant’s information and I couldn’t get it even though I stayed there for an hour. I still do not have it. And that patient also needs to go there and get documentation, something that was not the case previously.

So everything’s become much more complicated.

Yes. If you get what you need, you are fortunate. But this takes us back to where we were before, when people didn’t go to certain clinics because of stigma or because they’d be charged. The people [at the two LGBTQ-friendly] clinics who understood and knew how to treat them are no longer there.

NGOs give better service than the public health staff. The government was not supposed to rely this much on NGOs, but unfortunately they did. Now the government needs to make sure that the pills are accessible to people, because they’ll expire on the shelves if they’re not taken.

At least in South Africa we have the medication. Other African countries don’t. But now we don’t have the proper infrastructure to make sure that people are getting the service they’re supposed to. People are not supposed to ask us, “Can Desmond Tutu Foundation give us meds?” That’s not our service. It’s to investigate clinical products and make sure that the health care system has got access to …products. We cannot do everything. We’re an NGO and are fortunate that we are still surviving, but we can’t provide services that the government is supposed to provide. We have to do our best to make sure that we’re not in this mess ever again.

How likely or soon do you think that the South African government will step up and meet this need that has been taken away by the U.S.?

[cries] I am hoping that, especially for South Africa, that we are going to push much quicker. I belong to a network of 21 women from seven different countries in Africa. So we are holding our governments accountable, saying, “We are your people, your taxpayers. So our tax money needs to be used accordingly.”

We need to make sure that our governments create employment around these efforts. We can no longer depend on other [countries], because this is what dependence has led to for us. Like I said, South Africa is better off than other African countries because our government, not PEPFAR or other charities like The Global Fund, pays for treatment.

When we first heard that PEPFAR was being cut, I lost my breath. I am what I am because I am taking treatment. But now we are stuck. The price of treatment, which is not actually made here in South Africa, is going to skyrocket, because middlemen are going to make sure of it.

Meanwhile, I am dealing with [patients] who don’t understand what’s going on. From now on, when they get their meds, we’ll have to say to them, “If you’re not going to take your meds, don’t even take them home, because somebody else needs it.”

And those who do not use condoms—we’ll have to prioritize HIV treatment over condoms, because everything will be from our tax money. If prevention, much of which PEPFAR covered, is too expensive for us, then we’d rather invest in treating the people who have HIV already. Right now, PrEP is still available for people.

But you just don’t know for how long?

Exactly. So we’d rather mobilize treatment instead of PrEP. Because PrEP means you’re taking the pills that could’ve been by someone who’s already infected and needs those meds to survive.

Emotionally, what have been people’s reactions to these abrupt and draconian cuts from the U.S.?

It’s painful, Tim. Like, right now, you want to interview people. I’m in a hotel right now for a work trip and I’ve got people here with me who are also living with HIV. But they’ve lost their jobs. Last week, I was asked to invite people to come to our office to do an interview for American radio. I want to draw a picture for you. I called them into my office for the interview and it was done. And then when the [radio] lady was gone, they said to me, “We’re unemployed. We don’t even have money for bread. This person from America came to interview us. We need at least some kind of reimbursement to say thank you to us, because we used our money to get here.” I had to pay them from my own pocket.

Other than what I’m doing now, trying to paint a picture for American readers of what this has caused, what do you want us to be doing on our side about this situation?

Are you from Africa?

No.

Okay. I would say we need to do as much work as we can to negotiate with African governments. So they understand what the community is going through on the ground. I know the South African president said that these PEPFAR cuts are affecting only 17 percent of people with HIV in South Africa. But that’s about a million people, some of whom have lost jobs.

That is emotionally draining. One or two organizations alone cannot do this work. So how do we make sure that we sustain those people who know how to do the job but cannot now because they’re not getting paid? Communities rely on such people, those ground forces on the community level.

I feel such guilt over this as an American.

So does everyone [who is American and has supported PEPFAR]. We have to go back to the mindset we had in 2001–2002, before PEPFAR, and prioritize the things African people can do for themselves and not depend on other countries. Because now we are slapped—in the heart.

Other advocates have told me that even if the U.S. were to fully recommit to PEPFAR at some point, people in other countries wouldn’t trust us, because how can they trust a system that’s there one day and gone the next? Do you feel that way?

I do. But the painful part is that I don’t trust our own government [to pick up the slack]. I don’t. [cries] You’re talking about poor people who don’t have the money to pay for anything. And they are going to suffer. I’ve got my job and salary, but I am surrounded by people who are hungry. And being an activist is very heavy currently because you don’t even know the right words to say to the person to make them feel good.

It’s a lot to hear this from you. It’s one thing to read about it in the abstract and another to talk to someone who is so closely affected.

Yeah. It’s bad. We are like this. [She makes a choking gesture].