Forty years later, AIDS is past, present, and future

AIDS: 40 years later

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the start of AIDS in 1981. To me, a 60-year-old gay man who was a closeted college student when the epidemic began, 1981 seems like yesterday. But it’s not really yesterday. The world has changed a great deal in 40 years. And yet AIDS is still with us.

Worldwide, there are about 38 million people living with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Since the beginning of the epidemic, about 76 million people worldwide have acquired HIV, and some 33 million have died from AIDS-related illnesses.

Today there are highly effective treatments that allow many people with HIV to have decades of good health. But that rosy prognosis is far from uniform—better in North America, for example, than in sub-Saharan Africa, and better in some demographic groups than others, depending on factors like race, ethnicity, gender, income, and access to healthcare, to name just a few.

Today we have medications that can prevent HIV infection, but we still don’t have a vaccine (compare that to COVID-19, for which two vaccines were developed within one year after the virus was identified, with a third now available and more in the pipeline).

Today, AIDS is past, present, and future—and that is how we will explore it in the remainder of this essay.

The advent of AIDS unfolded like a movie montage of newspaper headlines. In the spring of 1981, there were rumors in New York City’s gay community about an exotic new disease affecting gay men. In May, a young medical doctor with a penchant for journalism, Lawrence Mass, wrote an article for the New York Native, a pioneering gay tabloid, seeking to get at the truth of the rumors. Mass interviewed Steven Phillips, an epidemiologist from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) who had been assigned to the New York City health department. Phillips confirmed that a number of gay men had been treated recently in New York City hospitals for Pneumocystis cariniipneumonia (PCP), a fungal pneumonia usually seen only in people with severely compromised immune systems. Wittingly or not, Phillips minimized the significance of these cases, telling Mass that the rumors of a disease affecting gay men were largely unfounded.

At the time, Mass’s article in the Native went largely unnoticed outside the local gay community. On June 5, however, the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), a publication of the CDC, published a brief item on recent cases of PCP in young gay men. I’ll quote in full the three sentences that go down in history as the Hindenburg of AIDS:

“In the period October 1980–May 1981, 5 young men, all active homosexuals, were treated for biopsy-confirmed Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia [PCP] at 3 different hospitals in Los Angeles, California. Two of the patients died. All 5 patients had laboratory-confirmed previous or current cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and candidal mucosal infection.”

That’s it. Forty-eight words. The first attack had been launched. The invasion had begun. The MMWR article was reported by The Associated Press, the Los Angeles Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle, spurring reports to the CDC from around the U.S. of similar cases of PCP, Kaposi sarcoma (KS), and other unusual presentations of severe infections among young gay men. Within weeks, members of the gay community were calling PCP “gay men’s pneumonia.”

Just a month later, MMWR reported 26 cases of KS in the previous 30 months among young gay men in New York and California (mostly San Francisco). A very rare skin cancer, KS is usually found in elderly men of Eastern European, Middle Eastern, and Mediterranean descent. Its appearance in these numbers among men so young, all of whom were gay, was highly unusual, and the doctors who identified these patients were quite alarmed. The cancer was also unusually aggressive—eight of the men died within 24 months of their KS diagnosis; by contrast, the mean survival time among typical older males with the disease was eight to 13 years.

Among the young gay men diagnosed with KS, several had serious infections, including PCP, toxoplasmosis, severe herpes simplex, severe candidiasis, and cryptococcal meningitis, as well as past or present CMV. The term “gay cancer” now joined the recently coined “gay men’s pneumonia” in the public lexicon. Cases of KS, PCP, or both, in conjunction with other serious infections, continued to mount in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, overwhelmingly among young gay men.

The KS story was picked up by The New York Times as well—the first mention of the mysterious new scourge in the nation’s touted newspaper of record. Key elements in the story of AIDS were already clear by then. One doctor quoted in the Times said that most cases had involved gay men with “multiple and frequent sexual encounters with different partners, as many as 10 sexual encounters each night up to four times a week.” In addition, a number of gay men with KS, PCP, and other serious infections had deficient T cells and B cells—components of the immune system that play a role in fighting infections as well as cancer.

The Times also noted that many of the young gay men with this striking and unusual cluster of diseases had reported using “drugs such as amyl nitrite and LSD to heighten sexual pleasure.” Amyl nitrite is poppers, and the belief that AIDS was related to poppers would take firm root in both the medical community and the popular imagination in the following years.

Experts did not know how or even if this cluster of KS, PCP, and other serious diseases in gay men was related. But members of the medical community who treated these patients and affected members of gay communities in the nation’s urban gay meccas of New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles could only surmise that something very, very bad was happening.

One August night, gay novelist Larry Kramer, then known especially for his groundbreaking 1978 novel Faggots, gathered scores of gay men to his New York City apartment to discuss the emerging health crisis. The guest speaker was Alvin Friedman-Kien, one of the dermatologists who contributed the initial case reports of KS in gay men. Kramer solicited contributions to support Friedman-Kien’s research, because there was no other funding readily available to confront the burgeoning crisis.

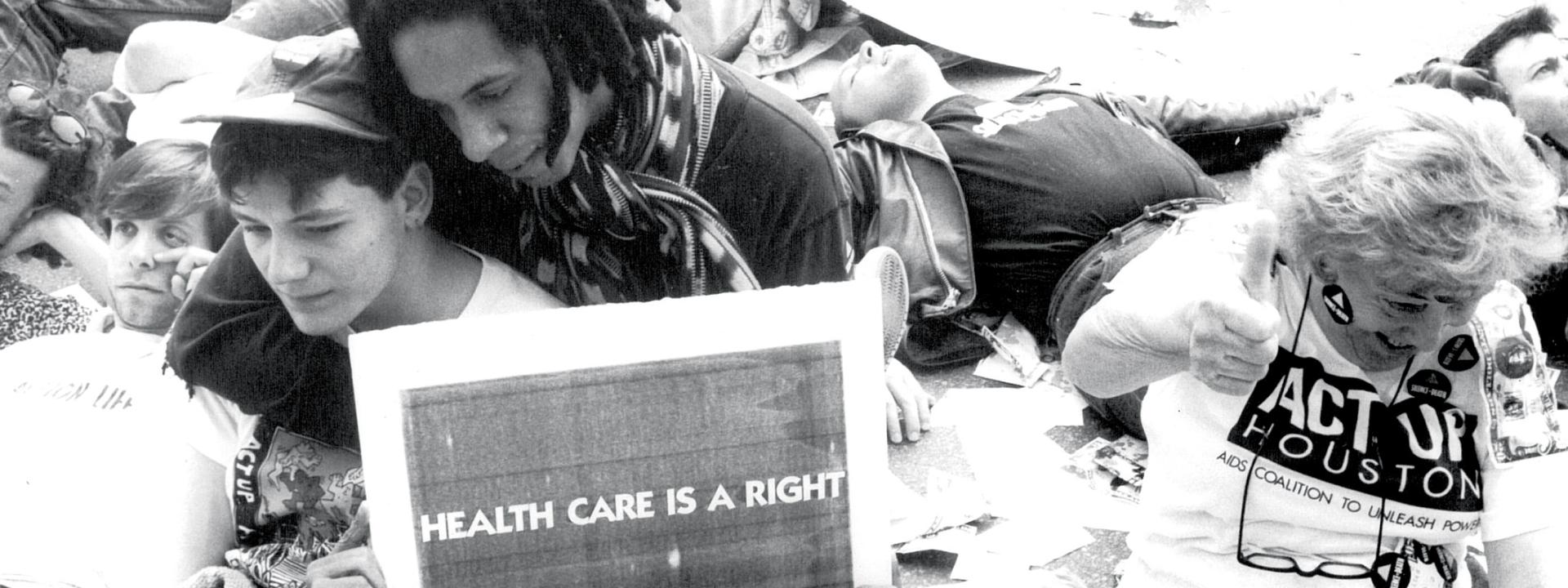

A series of meetings like this would ultimately lead to the creation of both Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) in 1982 and AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in 1987, both of which were spearheaded by Kramer, who remained an ardent (and often controversial) AIDS activist the rest of his life until his death at the age of 84 last year.

As winter approached, New York pediatric immunologist Arye Rubinstein treated five Black infants with signs of severe immune deficiency, including PCP. Several were children of women who used drugs and engaged in sex work. Dr. Rubenstein’s assertion that these children were suffering from the same condition that was being observed in young gay men was initially dismissed by his medical colleagues, but this would ultimately prove to be the moment when AIDS emerged in the Black community, driven among men, women, and children by sexual contacts, injecting drug use, and mother-to-child transmission.

Also that winter, Bobbi Campbell, a 29-year-old nurse and a member of the gay community in San Francisco, became the first to go public with his KS diagnosis, calling himself the “KS Poster Boy” and writing a regular “Gay Cancer Journal” column in the San Francisco Sentinel to chronicle his experience. To alert the community and encourage people to seek treatment, Campbell posted photos of his KS lesions in the window of a local drugstore. Two years later, Campbell would appear on the cover of Newsweek with his partner Bobby Hilliard, illustrating the cover story “Gay America: Sex, Politics, and the Impact of AIDS.” This was the first time two gay men were shown embracing on the cover of a mainstream national magazine. Campbell co-founded People With AIDS San Francisco in 1982, and a year later collaborated with men from across the U.S. to write The Denver Principles, the founding document of the burgeoning self-empowerment movement among people with AIDS. Campbell died in 1984 at the age of 32.

As the first year of AIDS drew to a close, there were over 300 reported cases of people with severe immune deficiency in the U.S., of whom 130 died by December 31. Cases had also been reported in Spain and the United Kingdom. Medical experts remained in the dark about what was causing the immune deficiency that laid people vulnerable to otherwise rare infections like PCP, cancers like KS, other serious infectious diseases, and ultimately death. The general public was still largely unaware of the emerging crisis. There had been no congressional hearings, no funding provided for research. The early center of gravity for the medical response was the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, where Marcus Conant and Paul Volberding co-founded the nation’s first dedicated KS clinic, and they along with their UCSF colleagues Connie Wofsy and Donald Abrams took the lead in treatment and research.

At the rate I am telling the story, this would be an excerpt from an 80,000-word book. We don’t have room for that here. And there are plenty of ways you can get the whole story—or many different parts of the whole story, as no one book or film or theatrical work can capture the complexity of the AIDS epidemic, its origins, its unfolding, its legacy forty years later. Let’s try it in 39 more sentences or less:

The founding in 1982 of both GMHC in New York and the San Francisco AIDS Foundation (under its earlier name, The Kaposi’s Sarcoma Research and Education Foundation).

The brief emergence of the term gay-related immune deficiency (GRID) to describe the outbreak, until the CDC came up with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), which stuck.

The opening of Ward 86 at San Francisco General Hospital as the world’s first dedicated outpatient AIDS clinic.

The popular use of the term “4H club” as shorthand to refer to the groups perceived to be at risk for the disease—homosexuals, hemophiliacs, heroin users, and Haitians (while the CDC did not coin the term, its use appears to derive from an MMWR article published in March 1983).

The DIY publication of the pioneering safer sex pamphlets Play Fair!, written by members of the San Francisco Order of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, written by boyfriends Richard Berkowitz and Michael Callen (a member of the gay male a cappella group The Flirtations).

The publication of The Denver Principles, the founding manifesto of the National Association of People with AIDS, proclaimed by a group of gay men who stormed the plenary stage of the Second National AIDS Forum in Denver.

The more-or-less simultaneous discovery of the virus that causes AIDS, by the laboratory of French virologist Luc Montagnier (1983) and that of U.S. virologist Robert Gallo (1984)—originally called human T-lymphotropic virus III (HTLV-III), and later renamed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

The closing of gay bathhouses in San Francisco (1984) and New York (1985).

The death of Rock Hudson due to AIDS-related illness at the age of 59, who left $250,000 in his will to help set up the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR), co-chaired by Elizabeth Taylor and medical researcher-cum-socialite Mathilde Krim.

The opening off Broadway of Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart at New York’s Public Theater, and the opening of As Is, by William M. Hoffman, the first play about AIDS to open on Broadway (1985).

The banning from school of Indiana teenager Ryan White, who acquired HIV through contaminated blood products used to treat his hemophilia, and who becomes an outspoken advocate for AIDS research and public education (1985).

The first public mention of AIDS by President Ronald Reagan, who called it a top priority and defended his administration’s (lack of) response to the epidemic (1985).

The birth of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, with the creation of the first panel by San Francisco AIDS activist Cleve Jones to honor his friend Marvin Feldman (1987).

The death of flamboyant pianist and showman Liberace due to AIDS-related illness at the age of 67. Unlike Rock Hudson, Liberace hid his illness, and his gayness, to the end of his life (his publicist maintained that he died of complications from a watermelon diet, until a court-ordered autopsy determined the true cause of death).

We are about out of space, and we are only up to the winter of 1987. AIDS at 40 is indeed a long and complicated tale, by turns grim, heroic, and at times even exhilarating (see either the original Broadway production, the 2003 HBO miniseries, or the 2017 West End revival of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America). We cannot close the cover of our MacBook, however, without mentioning three things. First, the formation of ACT UP in 1987, the activist group that used direct-action strategies and tactics to radically change the response of government, the medical establishment, and the pharmaceutical industry to AIDS. Second, the remarkable history of treatment for HIV infection (antiretroviral therapy), starting with AZT in 1987, passing through milestones like the advent of protease inhibitors and triple-combination therapy in 1996, and flourishing today with multiple classes of drugs and ever more safe, effective, and convenient drugs and regimens. And third, the ascendency of treatment as prevention in several forms—treatment of women during pregnancy and delivery, and of infants after birth, to prevent vertical (mother-to-child) transmission; post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) after a sexual or occupational exposure; pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), meaning the use of HIV drugs by people without HIV to prevent them from getting it; or virologic suppression in people living with HIV (today often referred to as “undetectable equals untransmittable,” or U=U, which is the concept that people with HIV whose virus is suppressed by effective treatment cannot transmit the virus to sexual partners).

One final thing that must be stated as we mark 40 years of AIDS: the continually evolving demographics of the epidemic. AIDS was first recognized as an outbreak among mostly gay white men ages 25 to 49 in a handful of urban centers in the U.S. Clinicians and epidemiologists soon realized that the epidemic also encompassed non-gay men, women, people of color, and children born to mothers with HIV. Moreover, they realized that HIV could be transmitted not only through sex, but through contaminated blood products, sharing needles to inject drugs, and from mothers to their infants during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding.

Today, the greatest beneficiaries of effective treatment and prevention for HIV have been gay white men in affluent countries—the very same men who first bore the overwhelming brunt of the emerging epidemic 40 years ago. That is a blessing; but we must always bear in mind that the AIDS epidemic still rages in specific regions and among specific populations the world over. On a global scale, the epicenter of AIDS has long since shifted to sub-Saharan Africa, followed by Asia and the Pacific (the Caribbean as well as Eastern Europe and Central Asia are also profoundly affected). Today, more than half of all adults around the world living with HIV are women, and HIV is the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age. Globally, young people (ages 15 to 24) account for about a third of new HIV infections annually. And about 1.8 million children are living with HIV worldwide. In the U.S., Black and Latinx people are disproportionately affected by HIV. Among all groups in the U.S., the rate of new HIV diagnoses is highest among those ages 25 to 34. The largest proportion of HIV cases in the U.S. continues to be attributed to sexual contact between men.

As we mark 40 years of AIDS, we still await a vaccine to prevent HIV, and a cure for people who are living with it. The remarkable development of vaccines to prevent COVID-19 has benefited immeasurably from 40 years of HIV research. Ongoing efforts to develop antiviral treatments for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, also rely heavily on the pharmacologic science of HIV—namely, the strategy of targeting viral proteins and using combinations of antiviral drugs, targeting different viral proteins, to more effectively and durably suppress or eliminate viral replication. Even the person leading the scientific and medical charge against COVID-19 in the U.S., Dr. Anthony Fauci, was tempered in the crucible of the AIDS epidemic. Similar observations could be made about the development of treatments—and in some cases cures—for hepatitis B and hepatitis C, as well as other viral infections and cancers. We as individuals affected by HIV and AIDS, and we as a society and a culture marked indelibly by this disease, have much to grieve, as well as much to be grateful for, at this moment in the history of AIDS.

Michael Broder is a gay, white, poz, Jewish, male, late-Boomer Brooklyn native (b. 1961). Columbia undergrad, MFA in creative writing from NYU, and PhD in classics from the CUNY Graduate Center. He tested HIV-positive in 1990, and started doing AIDS-related journalism while collecting unemployment insurance in 1991. He lives in Bed-Stuy with his husband and several feral backyard cats.