First of a series of studies on a twice-yearly injection for PrEP

Lenacapavir, an HIV prevention drug in development that’s injected every six months, has been found to be 100% effective in a clinical study of cisgender women.

This is reportedly the first time a phase 3 HIV prevention study has found zero new diagnoses. After an interim analysis an independent Data Monitoring Committee recommended halting the study and that all the participants be given the drug.

No cases of HIV were reported among the 2,134 women who were given lenacapavir, demonstrating the drug’s superiority over the two oral medications already in use for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—Descovy and Truvada.

“Twice-yearly lenacapavir for PrEP, if approved, could provide a critical new choice for HIV prevention that fits into the lives of many people who could benefit from PrEP around the world—especially cisgender women,” said Linda-Gail Bekker, PhD, director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Center at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and past president of the International AIDS Society. “While we know traditional [oral pills] HIV prevention options are highly effective when taken as prescribed, twice-yearly lenacapavir for PrEP could help address the stigma and discrimination some people may face when taking or storing oral PrEP pills, as well as potentially help increase PrEP adherence and persistence.”

The double-blind, randomized phase 3 PURPOSE 1 study enrolled more than 5,300 cisgender adolescent girls and young women ages 16–26 in South Africa and Uganda.

Among the 1,068 women in the study’s Truvada arm, 16 new HIV diagnoses were reported. There were 39 diagnoses among the 2,136 women taking Descovy. In both the Truvada and Descovy arms, participants took one pill of their respective medication each day.

Because Truvada and Descovy are longtime HIV prevention drugs, a placebo group was considered unnecessary and unethical, so background HIV incidence (the number of diagnoses expected in a population in absence of any medication) was used for comparison. Truvada, the first drug to be approved for PrEP in 2012, was used as a secondary comparator. Descovy has not been FDA approved as PrEP for cisgender women and was used in the study on an investigational basis.

Lenacapavir is also being studied in other groups. Results are expected late this year or early next from PURPOSE 2, being conducted in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Perú, South Africa, Thailand and the United States among cisgender men who have sex with men, and transgender women, transgender men and gender nonbinary folk. Recruitment is underway for PURPOSE 3, centering on cisgender women in the U.S., and PURPOSE 4, among people who use injection drugs.

More PURPOSE 1 data are expected to be presented later this year, particularly at July’s AIDS 2024 international HIV conference in Munich, Germany.

Lenacapavir was approved by the FDA in December 2022 for use as a component of HIV treatment—not as a complete regimen. Marketed under the brand name Sunlenca, it is taken every six months along with other HIV medications and is for people living with HIV who are heavily treatment experienced.

Another injectable medication, cabotegravir, in combination with the HIV drug rilpivirine, became the first FDA-approved long-acting complete HIV treatment in January 2021, under the brand name Cabenuva. In December that year, cabotegravir was approved for HIV PrEP, as Apretude. Long-acting injectables, however, have had issues with accessibility and insurance coverage, adding to health disparities already faced by people living with and vulnerable to HIV.

“We must not forget that proving efficacy is just the first step in the long path to equitable implementation,” said Aniruddha Hazra, MD, director of STI services at the University of Chicago’s Department of Medicine. “We have learned a lot these past few years with trying to scale-up long-acting cabotegravir, the largest challenge being cost and coverage. These obstacles will be no different with lenacapavir and unless we are able to overcome them, inequities in PrEP uptake and HIV diagnosis will persist, if not widen.”

It’s not yet known what Gilead’s plans are for getting approval of lenacapavir for HIV prevention.

“We expect to see a timeline that takes into account a full analysis of PURPOSE 1 data and the coming data from PURPOSE 2 from Gilead as soon as possible, and we urge regulatory agencies to prepare to fast track regulatory review,” said Mitchell Warren, executive director of AVAC, an international nonprofit that supports HIV vaccine and prevention development. “We also call on WHO [the World Health Organization] to be prepared to quickly include lenacapavir, if approved by regulatory agencies, in HIV prevention guidelines. There is no time to waste if we are to translate these exciting clinical trial results into actual public health impact and expand the toolbox of HIV prevention choices.”

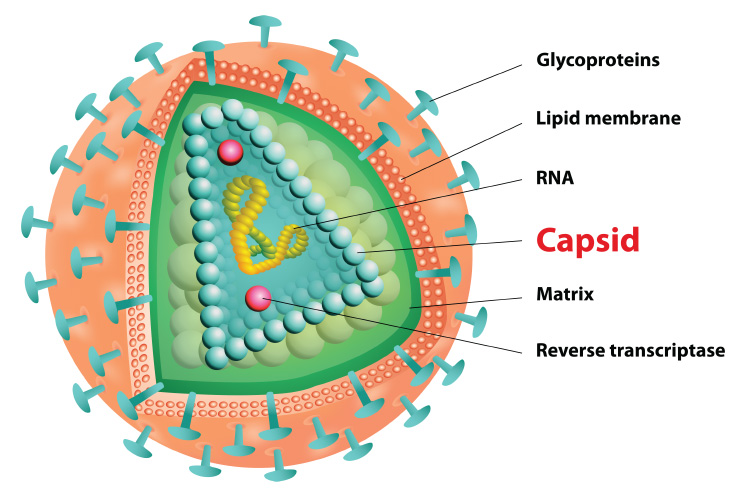

The HIV capsid, a protein shell that protects HIV's genetic material and enzymes needed for replication, is targeted by lenacapavir (illustration: iStock)

Manufactured by Gilead Sciences, lenacapavir is the first of a new class of HIV drugs—capsid inhibitors—which target HIV capsid, a protein shell that protects HIV's genetic material and enzymes needed for replication. Capsid inhibitors disrupt the capsid during early and late stages of the HIV life cycle.