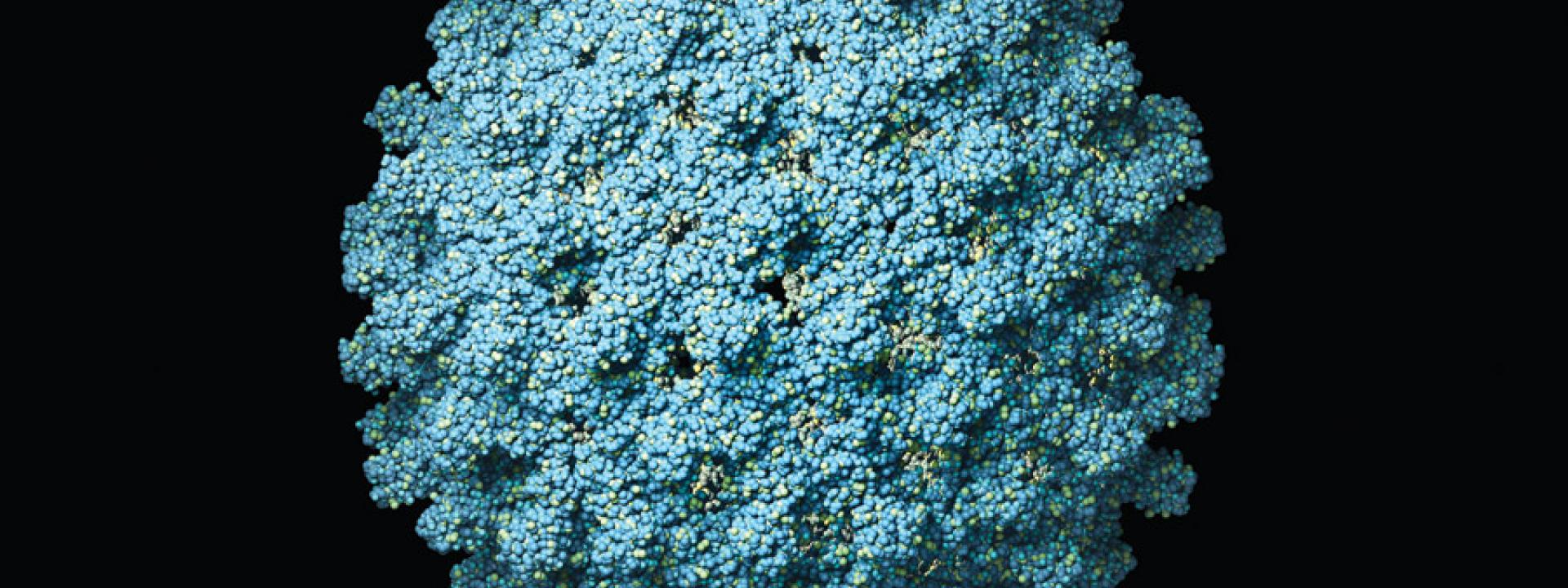

Another important virus to keep in mind

This year’s hepatitis drug guide takes on hepatitis B virus (HBV) in addition to hepatitis C. Both viruses commonly affect people living with HIV. Testing and treatment for both is important for the HIV-positive population and others vulnerable to HBV.

This is not an exhaustive review of all things related to HBV, but this article will cover four basic topics: transmission, testing, vaccination, and treatment. We’re not going to cover pregnancy in detail: That is a complicated subject that deserves an article of its own. Check out the Hepatitis B Foundation listed in the HBV resource section on page 57 for more information related to HBV and pregnancy.

An overview

HBV is a virus that infects the liver. It is the most common infectious disease in the world, with over 2 billion people worldwide having been infected with it in their life, and approximately 240 million of those are chronically infected (living with HBV). Worldwide, it leads to over 780,000 deaths per year. In the United States there are between 850,000 and 2.2 million people living with HBV, and about 10% of people living with HIV are co-infected with it.

Transmission

Hepatitis B is transmitted in much the same way as HIV: It’s spread when the blood, semen, vaginal fluids, or other body fluids of an HBV-infected person gets into a person who is not infected or protected by immunity (through vaccination or cleared infection). It is also commonly transmitted from mother to child during birth.

Only about 5 to 10% of adults exposed to HBV will be chronically infected. That said, HBV is highly infectious through blood or sexual fluids, so if you think you’ve been exposed to it and have not been vaccinated, you should go see a medical provider ASAP: There are ways to prevent infection after exposure (called post-exposure prophylaxis, or PEP). And of course, if you have not yet been vaccinated, see your medical provider or head to an STD clinic to start an HBV vaccination schedule. See below for more details about testing and vaccination.

Testing

Hepatitis C is often called the “silent epidemic,” as most people who have it don’t know it due to a lack of noticeable symptoms. The same can be said of HBV: Most people who get HBV don’t know it because it rarely leads to signs or symptoms in the acute or chronic stages of infection. Over time, as the liver gets damaged, noticeable symptoms may arise, but screening for the virus is the only way to be sure you’re infected or not.

Testing for HBV can be intimidating, especially when compared to some of the other testing you may have done for other diseases. When you take an HIV test, your results are either negative or positive for HIV antibodies. Hepatitis C testing is a little more involved: You test either negative or positive for HCV antibodies, and then do a confirmatory viral load test to confirm a positive result.

Hepatitis B testing is more complex. It is a blood test that looks for a marker or a series of markers to determine where a person is at on the spectrum of HBV infection (acute or chronic), if immune to it (through vaccine or natural immunity from prior infection), or vulnerable to infection and in need of vaccination.

Your medical provider will help you make sense of the results, but it is still important for you to understand them, too. The chart below provides you with the various results and explains what they mean.

Again, this looks intimidating: If you get a lab result without any explanation of the results, you can compare to the results listed above. Your medical provider can also explain the results. Check out the HBV resources section on page 57 for more information and HBV phone lines to help you make sense of the results.

Vaccination

Hepatitis B is vaccine preventable. The vaccine is safe and highly effective in preventing HBV, working in over 95% of people who get it. The vaccine is administered at 0, 1, and 6 months. This vaccine is effective for the rest of your life with no need for a booster shot in your future.

If a person already has HBV, the vaccination will offer no protection against disease progression and risk of liver disease. Sometimes, people get vaccinated without getting checked for chronic infection: Ask your medical provider if you have been checked for chronic HBV infection (or, if you are someone who was exposed to the virus and then cleared it, and are thus naturally immune) before starting a vaccination schedule.

Treatments

While HBV is preventable with a vaccine, to date there is no cure for it. There are treatments, however, that can help control and slow the virus from reproducing. These treatments can slow down the damage done to the liver and reduce the risk of long-term problems like cirrhosis or liver cancer.

While HBV is treatable, not everyone needs to be treated. HBV treatment is not recommended for someone in the acute stage of infection: Most people will clear it naturally and treatment doesn’t look to improve the chances of clearing it. If someone is chronically infected, but has normal liver function tests called ALT or elevated ALT with low or undetectable HBV viral loads, then they do not need treatment. While they do not need treatment, they should be monitored routinely and engage in healthy liver behaviors and activities.

Treatment for HBV is called for in anyone with cirrhosis, regardless of ALT or HBV viral load. Similarly, anyone living with chronic HBV who is undergoing immunosuppressive therapy should be treated to prevent an HBV flare-up. There are other varied scenarios where a person should be treated for HBV, but those conversations are best to be had with a medical provider. If you’re living with HBV and are concerned about whether or not you should take HBV treatment, talk with your medical provider.

Currently there is no cure for HBV. There are several drugs under investigation to determine their effectiveness and safety for treating and curing HBV. Stay tuned to POSITIVELY AWARE and other resources for updates on research on new therapies and cures.

For more information on HBV treatments, check out the HBV Drug Guide.

Conclusions

Hepatitis B is very common and a potentially deadly infection that leads to much suffering worldwide. The burden in the U.S. is also high, with new outbreaks and infections spreading due to injection drug use and mother-to-child transmission as a result of the opioid crisis. To date, we have no cure, but with increased vaccinations and screening we can eliminate HBV in the U.S. and beyond.

Serological Markers for HBV

What do they mean?

SEROLOGIC MARKER |

RESULT |

INTERPRETATION / MEANING |

|

HBsAg |

Negative |

Susceptible; get vaccinated |

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs |

Negative |

Immune due to natural infection; no vaccination necessary |

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs |

Negative |

Immune due to hepatitis B vaccination |

|

HBsAg |

Positive |

Acutely (recently) infected |

|

HBsAg |

Positive |

Chronically infected; monitor disease, prevent transmission to others, and if necessary, treat the infection |

|

HBsAg |

Negative |

Interpretation is unclear, 1. Resolved infection |

|

Serologic definitions |

||