Biennial reflections on creating cultural change

In 2014, at the first HIV is Not a Crime National Training Academy, in Iowa, participants hailed advocates in the state for successfully modernizing its outdated, stigmatizing HIV criminalization laws. When a presenter at the closing session asked “Which state will be next?” Positive Women’s Network - USA (PWN-USA) Colorado advocate Kari Hartel raised her hand on behalf of their state. “I remember seeing her hand go up,” Barb Cardell, also of PWN-USA Colorado, recalled, “and thinking, ‘Well, damn! Now we have to figure out how to pull this off.’ ”

Thus the Colorado Mod Squad (“mod” stands for “modernization” of the law), a diverse task force led by women living with HIV, was born. By the time advocates from 34 states and four countries came together for the second HIV Is Not a Crime gathering in Huntsville, Alabama, from May 17–20, 2016, they were celebrating the Mod Squad’s victory in the Colorado legislature—the second such win in the nation. As the new bill awaits the governor’s pen, there are 44 U.S. states where such stalwart advocacy is needed: where HIV stigma is still codified into laws, or sentence enhancements, that criminalize people for living with a health condition, and have terrible effects on public health.

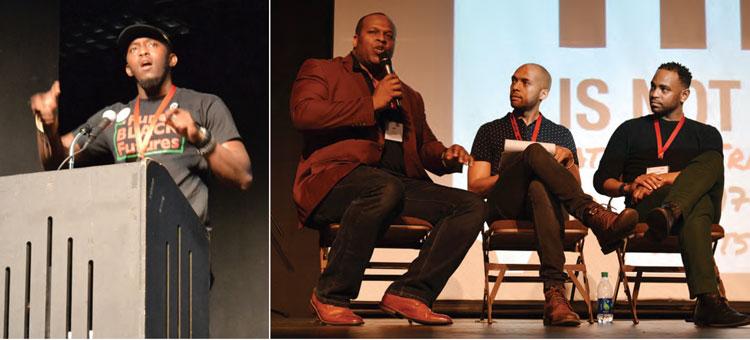

“The lesson we have learned from the successes in Iowa and Colorado is that people living with HIV must be meaningfully involved in the decision-making processes,” said Tami Haught, who led Iowa’s modernization efforts and was a key organizer of both training academies. People living with HIV made up more than two-thirds of the advocates that came to Huntsville to learn how to fight HIV criminalization in their states. There were nearly 300 attendees overall—almost double the number in 2014.

A biennial event provides a critical benchmark for observing the development of a project, a community, or a movement. “[Since 2014], the effort to combat HIV criminalization has become linked in important ways with related movements addressing racial justice, sex work organizing, drug policy, and penal system reform,” said Sean Strub, executive director of the Sero Project, which, along with PWN-USA, co-convened the gathering. “It is increasingly becoming an interwoven quilt of advocacy for profound change in how we understand, pursue, and embrace justice.”

POSITIVELY AWARE asked presenters and participants at the Huntsville training academy to reflect on the progress they wish to see in this epic human rights endeavor in the next two years.

The growth and (hopeful) success of more statewide campaigns. “It took Iowa five years,” Strub explained to activist and blogger Mark S. King in a video interview at the training academy. “Colorado did it in two years.” (Watch the video at youtube.com/watch?v=Dpw7d0AuJ80.) Though a number of states, including Michigan, Georgia, Idaho, and Florida, are now home to nascent campaigns (in part thanks to the 2014 training), predicting the next success story is challenging. “Each state is different, from different laws to different legislative makeup,” said Haught. “We were able to provide basic advocacy strategies for everyone; it is then up to state advocates to adapt to fit their specific needs.”

Nina Martinez, who engages in HIV decriminalization advocacy in Georgia, would like to see advocates look beyond state legislatures. “Why aren’t there more constitutional (judicial) challenges to HIV criminalization laws? Why aren’t we appealing to heads of state (executive branch)?” she asked. “Criminalization is the most stigmatized of all advocacy issues, and we’re going to have to get creative.”

More available data on the realities and impacts of HIV criminalization. To make their case, advocates need data supporting their messages. Legal and social science research on HIV-related criminal cases is sorely lacking. But committed investigators like Trevor Hoppe of the State University of New York at Albany and others, as well as institutions like the Center for HIV Law and Policy and the Williams Institute at UCLA Law School, have contributed to this pipeline of research.

“We need more data on the public health harms of HIV criminalization in the US context,” stated Edwin Bernard, one of the world’s foremost anti-criminalization advocates and the coordinator of HIV Justice Worldwide. “Rights-based arguments—convincing as they are for advocates and our intersectional allies, and the reason many of us do this work—may not be enough to change the hearts and minds of policymakers.”

Embracing linkages with intersectin communities and movements. “Many of the communities impacted by HIV criminalization are generally at risk for being targeted by law enforcement, may regularly face police brutality, and are unlikely to have good representation in a court of law,” said Naina Khanna, executive director of PWN-USA. “We can’t fight HIV criminalization as a single battle, without looking at these other issues impacting our community.”

According to Ashton Woods—a Houston-based activist in many intersectional communities, including HIV, LGBT, and the Movement for Black Lives—the HIV decriminalization movement needs “partnerships with groups, organizations, and persons that are already doing the work around [other forms of] criminalization. That provides a foundation and infrastructure to build a real-time system for information sharing, response to incidents, and a cohesive way to speak with legislators.”

Derek Demeri, a sex worker rights advocate in New Jersey, looks forward to the strengthening of these alliances. “Given how these laws are overwhelmingly applied to sex workers across the country,” Demeri said, “it is time the sex work community deepens our involvement in these strategic meetings.”

Diane Burkholder, an anti-oppression consultant and co-founder of One Struggle KC, which does Movement for Black Lives work in Kansas City, worked in HIV service organizations for many years. She is wary of what she sees as the directive in HIV decriminalization advocacy to “play nice” with lawmakers. “I find this very interesting, considering the momentum of those involved in the Movement for Black Lives,” said Burkholder. “If Black folks are disproportionately affected by HIV, especially Black youth … why aren’t we taking their lead?

“This movement against HIV criminalization laws must be made palpable for folks who don’t want to engage in conversations about HIV.”

On the HIV community side, urged Maxx Boykin, manager of the HIV Prevention Justice Alliance and a leader in the Black Youth Project 100’s Chicago chapter: “We have to start having conversations about: What is anti-Blackness? What is the war on drugs? How do many of our laws already affect us in racist ways?

“When we talk about this in the overall context of the war on drugs, and the criminalization of Black bodies,” he added, “that is where HIV decriminalization, to me, comes in. … I don’t think that a lot of people who have had wins in this arena are ready for [those conversations].”

Marco Castro-Bojorquez—a California-based filmmaker and a community educator at Lambda Legal, points out the importance of defining and outlining what intersectionality (the idea that multiple aspects of a person’s identity simultaneously impact their life and outcomes) means for advocacy work. He suggests that, “advocates, lawmakers, and the community in general can have a common understanding … to address the fear of the unknown that people have when they hear terms like ‘intersectionality’ or ‘interlocking oppressions.’ ”

“Greater attention to the nuances and complexities of modernizing versus repealing laws” is another of Bernard’s expectations for the movement to end HIV criminalization in the coming years. Boykin agrees: “There needs to be more education on what is true decriminalization,” he said. “In mobilizing the communities that are most impacted by HIV, I don’t believe you will get large amounts of our communities coming out [against HIV criminalization] when we talk about simply modernizing laws that can still harm us—that can still be used to criminalize young Black people.”

Demeri has similar concerns about the compromise inherent in talking about modernizing laws, rather than working to get rid of them altogether. “Until these laws are repealed … the language will still be manipulated and distorted as a means to arrest people who are looked upon as ‘vectors of disease’.” He warned: “If you want to include the sex work community, then do not expect our involvement, only to throw us under the bus later, as some advocates have done.”

Greater attention to how advocacy work is done. At the training academy, conversations emerged regarding models for engaging in advocacy in ways that are just, growthful, and creative, that resist interpersonal violence and support building connections within and across communities, as part of a strategy for ending HIV criminalization.

Randall Jenson, director of the LGBTQ media company SocialScope Productions, presented on the anti-oppression, trauma-informed, and harm reduction frameworks that have been central to his years of work with LGBTQ and HIV-positive survivors of violence—and all LGBTQ people, Jenson asserts, are survivors of the traumas of homophobia and transphobia. These frameworks open up space to address the fact that even people in the same community can potentially perpetrate harm with respect to one another, and can have different experiences of the dynamics of privilege, structural power, and oppression. Community members can also mobilize to support and help one another heal.

“Harm reduction would say: How to reduce the harm and the trauma that this person is going through? How to meet them where they are at?” Jenson envisions communities, and movements, where these approaches are incorporated at all levels of work, with firm commitments from leaders—and attention to explaining to members what these approaches mean. “We cannot assume all are coming in with the same level of understanding,” Jenson said; “there has to be room for ground work.”

Woods also supports “anti-oppression models that have embedded education on privilege, life chances, and other factors that vary by race and gender.

“Many good people out there want to do this work,” he said, “but they often drown out the voices of those most affected by current issues surrounding HIV.”

Castro-Bojorquez would like to hear more advocates expound on the language around “cultural factors” that negatively impact HIV outcomes—and use culture as an organizing tool and a positive force. “Why don’t we look at infrastructure and access,” he said, “and the cultural capacity of those folks that have no problem diminishing the only thing that keeps us going?”

Micky Bradford, regional organizer for Transgender Law Center and Southerners on New Ground, summed up HIV criminalization in this way: “The problem is both legislative and cultural. It will take a movement of radicals, artists, and ‘angelic troublemakers,’ as Bayard Rustin coined, to end state violence against all our people—but especially transgender and gender-nonconforming folks living with HIV in the South.

“What is a law,” Bradford said, “but the culture of the time crystallized and executed?”

Olivia G. Ford has been engaged with HIV-related media since 2007. She currently works as a freelance editor and writer, and is based in New Orleans.