Documentary tells the stories of young people born with HIV

“We were trying to make sense of it all before we could even fully develop into who we were as people … and these experiences have shaped our lives for better or for worse,” says filmmaker Grissel Granados in a voiceover for We’re Still Here, a short documentary that tells the stories of five young adults who were born with HIV back in the ’80s.

“This community has really been forgotten,” said her co-producer, John Thompson, a social worker and activist who works with Granados at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles. “One of the first things people say when you talk to them about perinatally infected youth is, ‘Didn’t all those babies die in the ’80s?’ This film was created to raise the awareness that this community is still here.”

Born in Mexico City, Granados was not diagnosed until she moved to Los Angeles at the age of five with her mother and sister, following the death of her father from HIV-related complications. Her mother, Silvia Valerio, traced her infection to a blood transfusion; she remains active as an advocate for people living with HIV, as well as working as a peer navigator at Bienestar in Los Angeles, where she focuses on transgender women.

Granados has talked publicly since she was 12 about growing up as a child who was born with HIV. In her journey—including her appointment as one of the youngest members of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS (PACHA)—she realized there was little awareness about this chapter of the epidemic, the children born with the virus who survive to this day. She also felt a need to reach out to others who shared her experience.

“The way we were told [about having the virus] also impacted our relationship with our own HIV and how open we were about it,” Granados noted in the film. “Those of us who received positive messaging grew up embracing our status at a young age, while those who grew up receiving stigmatizing messages grew up with more fear … shame.”

In We’re Still Here, poet and musician Mary Bowman reads her poem “Dandelions,” in which she first publicly revealed her positive status, and which also shows her strength.

Playing guitar in a punk rock band helps Nestor Rogel survive not just the virus, but the many demons of his past. “When I was younger, I thought it didn’t matter what I did, I was going to die. I didn’t really see a future for myself,” says Rogel in the film. Taking his cue from one sister’s advice, he says, “I can choose to live a happy and normal life, or I can choose to let the weight of the world sink in and swallow me up.”

Alison Luker is now a wife and the mother of three small children. She talks about how as a child, she only felt open and free while at Camp Laurel, where she met other children living with the virus. “I felt safe and secure at camp, but I knew that when I went back home I would have to… face realities. I was back to the world of stigma, where I was the outcast again.” Granados met both Luker and her brother Jimmy, who passed away in 2013, at camp. The documentary is dedicated to him.

Artist and dancer Kia Michelle Benbow, aka Kia Lebeija, talks about bringing “Disney” colors to her photographs relating to HIV loss, including the death of her mother. She talks about taking medicine, disclosure in school, and her own mortality after the death of her “super woman” mom.

“In the ’80s and ’90s,” Granados says in We’re Still Here, “while people were watching their friends, family, and lovers die en masse, we were there too. The friends we lost were other kids, and the family we lost were our parents and siblings.”

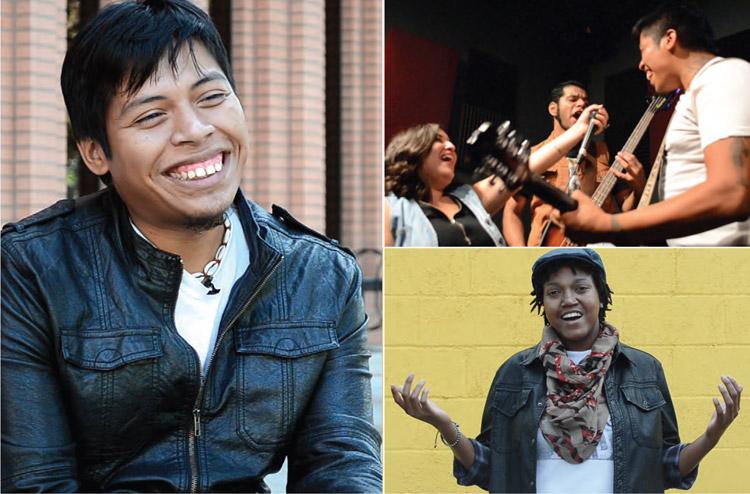

Filmmaker Grissel Granados. FROM LEFT, TOP TO BOTTOM: Nestor Rogel; Mary Bowman; Midnight Urge rehearses.

In her interviews and in the art produced by the young people in the film, there’s a range of themes such as being ostracized and the death of their parents. Granados, however, wanted to show their strength and triumphs as well. She said stories about living with HIV too often get stuck in tales of trauma. “For me,” said Granados, “one of the important parts about the film is focusing more on the resilience that people have.” It provides, she added, “a different narrative” for talking about people living with HIV, and “the characteristics that we have, which is more than all of the challenges and all of the trauma that we have faced.”

Granados found that they all used creativity as an important part of their life, “whether it was art, music, poetry, or family.”

Another similarity was that everyone talked about the death of their mother, except for Granados, because it was her father who had died. “As children, it was our parents telling our stories,” said Granados, “but in this situation, it is our opportunity to tell the stories of our parents. So I think the film demonstrates not just how HIV impacted children since the beginning of the epidemic, but also women and people of color.”

“It comes out through the stories, a division between different members of the HIV community,” said John Thompson. “These aren’t just the stories of people born with HIV, but they’re the stories of women living with HIV, of communities of color, the stories of how HIV is connected to poverty and to other kinds of social problems. It’s really a way to talk about those intersections and to build bridges rather than maintain those divisions.”

Thompson and Granados each earned a master’s of social work from the University of Southern California; at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Thompson is a clinical social worker working with youth and young adults living with HIV, while Granados works as a program coordinator in prevention. Part of her work is to oversee a prevention project aimed at gay and bisexual young men of color, as well as transgender youth of color. In their work, both have noted a misunderstanding among medical providers about the existence of adults who were born with HIV, and as a result, a diminished ability to address the needs of this population, such as addressing sexuality and childbearing. They hope that We’re Still Here can serve as an educational tool for both providers and advocates.

They also felt the need to connect the members of this neglected group, whose stories are rarely heard.

“We hoped to create a sense of community in this population,” said Thompson. “Grissel needed a way to connect with other people that were also born with HIV in the 1980s.”

It appears that others born with HIV needed her too. “People have reached out to us after seeing the film,” she said, “to ask whether there are any resources or any spaces for them to connect. There really isn’t anything.” She said they see that as another goal, how to support a digital space for people born with HIV to connect with each other and resources for providers who want to know more about this population and how to work with them.

For more information or to schedule a screening, go to werestillherefilm.com.